Imitation of Life: a pulp fiction milestone in spite of itself.

IMITATION OF LIFE, is one of those stories that touches a chord for audiences in our multi-racial society. It is an allegory that builds its own importance out of its own failings, tells us truths with its lies, and thus leads us to understand who we are in spite of ourselves. For that reason, it has become a fundamental element in American film history, both in its 1934 version and in its 1959 remake.

I don’t know how typical of America the local movie theater of my childhood was, but certainly, to me it was America. The Congress movie house on St. Johns Place in Crown Heights (now long gone) showed a lot of movies I wanted to see, horror films like The Blob and The Thing that wouldn’t Die, the Three Stooges and cartoons, and things I definitely did not want to see: mature stuff, like A Star is Born with Judy Garland, and oddly sensational things, like Imitation of Life, and the similarly themed, “I Passed for White.” I remember Imitation of Life being especially buzzworthy, but I never figured out what the buzz was all about.

Now, through the magic of Internet, I have finally seen that 1959 film, Imitation of Life, starring Lana Turner, and it brought up a surprising mix of emotions. I smiled and cringed at the same time, throughout the entire film. In this overwrought tearjerker, the story meanders from illogical to idiotic to absurd, but at the same time, it is unfailingly fascinating, as it dealt with the insidious racism that permeated all levels of society at that time. I got an idea why this particular film caused such a stir in 1959.

My curiosity was piqued and I decided to investigate a bit more. I coupled this with a viewing of the original film from 1934, giving me an even better view of how the racial divide evolved during the mid 20th Century.

The Novel by Fannie Hurst

Let’s start at the beginning. The novel, Imitation of Life, first appeared in 1933. It was written by Fannie Hurst, a well known writer of popular fiction at that time, and it was an immediate best seller. Reading the excerpts that I can find on the internet, I am curious about this novel, but not curious enough to want to read it through. The story seems hackneyed, and the writing is strange, dated and almost unreadable at times. A few lines describing the main white character’s widowed father:

“Since (his wife’s) passing, Evans Chipley was somehow, to his daughter, looking so dwarfed. Almost as if he had shriveled into his clothes and hung in the middle of them like a spider close to the center of his web. Poor Father. Life for him must be made to proceed as closely as possible to the pattern she had woven about his fastidious little needs.”

It appears that Fannie Hurst wrote a cliché ridden pulp novel, an imitation of literature, so to speak, but it turned out to be an imitation of American race relations, as well, and that was its value. The novel would have probably run its course and faded from memory, like the rest of Hurst’s oeuvre, except for the new life breathed into it by the film version, one year later. This first Hollywood version of Imitation of Life was an elaborate production directed by one of Hollywood’s most prolific directors of that time, John Stahl, and it featured one of filmdom’s biggest stars, Claudette Colbert.

The 1934 film, directed by John Stahl

To modern eyes, the 1934 film is a very eerie and odd Imitation of Life. In this version, two struggling single mothers, one black and one white, (played by Louise Beavers and Claudette Colbert) with daughters the same age, team up to face the world together to rise out of poverty. Never mind that “teaming up” meant that the black woman would serve as the white woman’s maid, while the white woman becomes fabulously wealthy peddling her maid’s pancake mix. To be fair, Colbert’s Beatrice Pullman has a good business plan and she works hard selling the mix in a shop and through mail order, but the unavoidable ugly fact remains that Beatrice ends up owning a beautiful home and living in grand luxury selling “Aunt Delilah’s” pancake mix, while the Louise Beavers character, Delilah Johnson, still lives in the same old maid’s quarters, with little share of the profits and waiting on her “mistress” hand and foot, all the while churning out the pancake mix! The inequality is accepted not only as the status quo, but as inherent and perpetual. The two daughters are brought up under the same roof, but under completely separate conditions. One to be a rich, spoiled heiress, and the other to be a poor worker. But that apparently was not a problem! The real problem, we are led to believe, is that the rebellious black daughter, Peola, played by Fredi Washington, is so light skinned that she can pass for white, which she does as soon as she can, and in so doing, violates one of the fundamental pillars that held up bi-racial America. She defiantly rejects her black mother and runs away to pass for white in the big city. It seems that Peola, in passing for white, has lost her soul, and that is what we are supposed to fret about as we watch this horror show.

Although the basic tension of the story is between black mother and daughter, the focus is always on Claudette Colbert. She was a sophisticated actress and she plays her enlightened white woman role with an entertaining flair. It is a noteworthy performance, given that we are in 1934, close to the beginnings of “talkies” when the art of movie acting was still in its infancy, and still heavily influenced by the overtly histrionic traditions of stage acting and silent film mime. And indeed, Colbert was no stranger to the emoting standards of her time, so her character is still a bit stilted, oozing good intentions as she merrily lives off her friend’s talents. It doesn’t help that the demands of the Hollywood dream factory during those Depression years dictated an aura of affluence for the star Claudette Colbert, and the visual conventions of that time, when realism was still a dirty word, also necessitated keeping the star made-up, powdered and painted and coiffed even as she slept. She wears silver lamé gowns while her maid wears a uniform, in the kitchen churning out the pancake mix. Her black maid and ostensible business partner,

Louise Beavers, attempts to give her character some depth, and she is very convincing in depicting the abject social conditions a woman in her position would have to face. Beavers’ acting is one of the first attempts to use film to simply juxtapose real characters and this uncivilized reality, and the effect is revolutionary. The film says nothing unconventional, but by its very existence, it is daring and courageous for its time. Nevertheless, it is still Hurst’s silly and retrograde story. The basic message to blacks in that story seems to be, “know your place and don’t act too uppity, or you will suffer.”

Thus, the story is working on several contradictory levels, each one reinforcing the other by its very opposition. The more ridiculous the story, the more intense the human suffering. We are expected to empathize with the black maid to a certain point, and then stop at the brick wall of segregated aspirations. We are supposed to disapprove of the black daughter’s rebellion while we non-judgementally observe the injustice she is expected to live under. This logic doesn’t work, and the underlying tension is palpable, however hard it would have been for those contemporaries to put into words. In fact, so much of the pathos in this situation is left unsaid, that we the viewers are able to fill in the blanks in any way we want. The story had a truth and an importance beyond its own artifice, touching on something raw and painful just below the surface in different ways, depending on who we are. It was not something easily explained but it was felt quite clearly, by African Americans and by whites, as well.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of Harvard University, as quoted in the Duke University Press edition (2004) of the novel: “Although it’s a ‘white’ novel, Imitation of Life is certainly a part of the African American canon. No film was more important to me as a ‘colored’ child growing up in West Virginia…”

Fredi Washington

One of the most remarkable (and remarked) aspects of the acting, was the extraordinary performances given by Louise Beavers as Delilah, and by Fredi Washington, as Peola, her light-skinned daughter. In their review of Donald Bogle’s book, “Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks,” Matthew H. Bernstein and Dana F. White state that the 1934 film, “… boasts two black actors transcending their flatly scripted roles. Even the film industry trade press and major white northeastern newspapers expressed surprise at the power of Beavers’ and Washington’s performances.” (“Imitation of Life in a Segregated Atlanta,” in Film History: An International Journal, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2007). Bernstein and White also state, “At the same time, the film’s popularity with black audiences is well-known: Imitation of Life was a cultural event, a watershed. Bogle notes that ‘Black ministers preached sermons about it while black intellectuals wrote about the film as well.”

It seems that the process of filming this story put it through a strange metamorphosis; the scenes convey far more than the superficial meanings the writers put into them. As the story passed through other hands, as it was retold over and over again, by screenwriters, director, cameramen, and became interpreted and re-interpreted over again by the actors and in the minds of the movie audiences, it took on more and more of a life of its own, and it became more imbued with the knowledge and experience that we all, as members of this multiracial society, bring to it. It underwent a process of mythification. It was art, and that is what art does. It sheds the limitations that its creators have put on it, and it becomes an entity on its own, with its own array of meanings, aesthetics and values.

The 1959 film, directed by Douglas Sirk

Twenty five years passed, and the story was revisited in 1959. This version stars Lana Turner, Juanita Moore, Sandra Dee and Susan Kohner in the four female roles. America and Hollywood had changed in that period, but there were still many intricate rules, prohibitions, taboos and fetishes. Imitation of Life was still a hot button connected to something deep, inexplicable and upsetting about America.

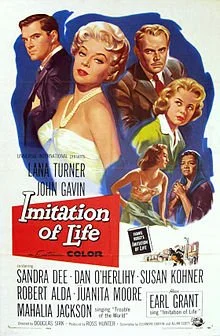

This poster for the 1959 film would barely give you an idea what the true story of this film was. The Hollywood publicity departments were not ready to give black characters the central place in any general audience film advertising. This, despite the fact that the director and screenwriters had made every effort to highlight the story of Delilah and her daughter Peola in the film.

For the visual element, something more glamorous and upbeat was needed in the America of postwar economic miracle. Now the white woman, Lora Meredith, played by Lana Turner, has become a theater actress, and a tinselly celebrity context is introduced, a change which mercifully eliminates the distasteful business relationship of the two women. Everything is much more visually appealing, and of course, colorful for this lavish production.

In those 25 years since the earlier version, few things had changed materially in the black/white relationship. For instance, the imagery in the publicity material for the 1959 film still focuses almost exclusively on the white performers, even though the real story is among the black characters. An ad campaign that pushed black actors to the front would have been box-office poison. However, there was a new sense of critical social analysis and a greater sense of social justice. Thus, certain changes were needed to make the story palatable to mid-century viewers. The white woman starts out a bit more convincingly poor, and she brings the black woman to live with her in a working class flat, rather than Colbert’s lovely suburban digs. Nevertheless, the basic mythology was never weakened. The black woman, Annie, played by Juanita Moore, is still the maid. She is allowed by the writers to improve her lot a bit, and later in the film, she refers to the large nest-egg of money she has amassed over the years. More importantly, the blatantly racist exploitative pancake business relationship has been abandoned, and now Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) gains her wealth more honestly through her own theater work.

Lora Meredith, the newly renamed Beatrice Pullman, is still a positive, sympathetic person, but far more nuanced. She is proud of her openmindedness, but we learn that she is a bit more racist that she realizes. She says to Annie, “I didn’t know you had any friends,” and this one replies, “Oh, I have many friends. You just never asked.” This is later reinforced by the image of Annie’s large funeral where indeed many hitherto unseen friends mourn her death. We also get a glimpse of the ruthless energy of Lora Meredith’s ambition, when she immediately falls in love with the first powerful Broadway playwright that she meets, thus guaranteeing her career. There is nothing in the words themselves that Lora speaks to show that she is anything but sincere in her love, but it is to the great credit of Lana Turner and a very talented director, that she clearly conveys the ambiguity and oddness of this turn of events. This director, Douglas Sirk, a filmmaking émigré from Nazi Germany, understood this American story from his unique angle, and using this conventional Hollywood writers’ mill script, he managed to make this film his signature Hollywood piece.

Another important change in 1959 is the shifting of more emphasis onto the black characters, who are indisputably the gravitational center of the story. Both Moore and Kohner get much more film time than did Beavers and Washington.

Susan Kohner

And in 1959, there is more playing toward the youthful audience, with both daughters’ stories more prominent, one for good reasons and the other, not so good. Sandra Dee’s star status and her scenery chewing performance which seems like a throwback to the 1934 era, make her impossible to miss, and sometimes it is necessary to try to see around her and listen past her voice to keep up with the story. She was an A-list Hollywood starlet, of course, and it seems no one has told her that she is there simply to give an excuse to bring on Kohner, whose compelling story is the true nexus. Now when we see the black daughter padding around the house nervously while the whites have an elegant dinner party elsewhere in the same house, her agitation is more fully developed psychologically, and it rings true. She is allowed by the script to give voice to her anger at times. We can perceive and understand her inchoate outrage, rather than tsk at her inarticulate pouting, as in the 1934 film. Susan Kohner’s seething portrayal of Sarah Jane is quite artistic, and it seems to tap out the whole mythical key to this drama. She may not be the main character of this silly tale, but she is the dead-serious protagonist of this allegory, and Kohner knows it. The critics knew it as well, and she was nominated for an Oscar (losing to Shelley Winters), and won a Golden Globe.

Another innovation is the elevation of the black musical interludes from the folkloristic level of the 1934 film, to a more dignified, professional level in 1959, reflecting the heightened awareness of the importance of black musical art in American culture. Whereas the spirituals are sung in the background by an unseen choir in 1934, as an atmospheric exercise in ethnomusicology, in 1959, Mahalia Jackson is showcased, singing Trouble of the World, in the funeral scene. She is front and center, singing to the film audience, and this is significant, because it demonstrates how Hollywood has come to recognize at this point that American black music speaks to all Americans. We are not just listening to the sounds that comfort the black mourners, but rather listening to the sounds that comfort us all. Click on the Youtube link below to hear this tremendous performance.

If it were filmed today?

Maybe it’s time for a new version of Imitation of Life, more than 60 years later. Only this time, I suspect that the focus would shift even more dramatically, to the one character that truly speaks about the enigmas and paradoxes of our world: the daughter who “passes.” Even today it would be a difficult story, one that would raise painful controversy and conflicting emotions. Maybe a new version would use Hurst’s “Imitation” as simply a story within a story, and focus on the real life trials of the actresses who play the key roles. Both Fredi Washington and Susan Kohner faced great pressures and injustices as actresses because of their ambiguous position in a segregated film industry. Susan Kohner’s story is all the more intriguing, considering that she was not African American at all. Her mother was Mexican-Irish, and her father was Czech Jewish. It’s unclear what, if anything, she was passing for, making the racial stigmatization she faced all the more puzzling. A film about their own lives would be fascinating. Something similar has already been done in the made for TV biopic, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge, for which Halle Berry won both an Emmy and a Golden Globe.

Every society finds its myths. There are basic problems, ironies and paradoxes in every society that can be expressed only through art. They are immune to logic, for logic can never explain the love hate relationship we all have with the frailties of human existence, the weaknesses that inform our creativity, and thus, our art and our beauty. Imitation of Life is a flawed story: maudlin, unrealistic, shopworn and naïve, but it deals frankly with one of the most basic ironies of U.S. society, and that is the symbiosis between Europe and Africa in our culture: white and black. And at its core is an old primal fear of racist society; Blacks passing for Whites. We may not fear this so much as in the past, but it does make people of all races deeply uncomfortable to talk about. Perhaps in the new version, we would be courageous enough to really explore the dilemma of this young woman’s fate.

Images are used here under the Fair Use provision of US copyright law.